A story about resilience, responsibility — and how we might reframe our return to the oceans, mountains and forests of this remarkable archipelago.

If you encounter a sea turtle in the sparkling waters of Hawaii, stay a respectful 10 feet away. Refrain from swimming above or beneath it. And should the turtle begin rubbing its eyes with its fins, that’s a sign that it has grown weary of your (understandable) fascination with it. It’s time to snorkel on.

This is just a smattering of the ocean know-how I glean from my guide Oliver Hodous, standing in the dappled shade of a Kiawe tree on Maluaka Beach before setting off on a kayaking tour along the south Maui coastline. The first 45 minutes of every three-hour Hawaiian Paddle Sports tour is devoted to education. We start with a primer on local reef fish (including parrotfish, which help maintain the island’s brilliant white-sand beaches by excreting the coral they eat) and review key ocean-conservation tips (a sunscreen labeled “reef safe” isn’t reef safe if it contains anything other than the minerals zinc oxide or titanium dioxide).

I also develop a cursory understanding of — and deeper appreciation for — Hawaiian culture and the poetry of its language. It is composed of only 13 letters plus the ‘okina, a punctuation mark resembling a reversed apostrophe that’s treated like a consonant. Many Hawaiian words convey more than one thing. “‘Aloha’ is more than ‘hello,’” Oliver says. “It is the essence of being, and it means ‘the breath of life.’ It’s a greeting of mutual compassion, like saying, ‘I breathe, you breathe, we are one person.’

I think about this as we push our kayaks out into the ocean, and I realize that the lesson on the beach has enriched my experience on the water. When I lean back to admire the view of the small volcanic island of Kaho‘olawe under a cloudless sky, I recall what Oliver shared about its past as a bombing range for the U.S. Navy. Today, its surface is riddled with craters, unexploded missiles and contaminated soil — though efforts are being made to protect Kaho‘olawe’s many sacred archeological sites and to rewild it with native plants. Later, when I pull on snorkel gear and slip out of my kayak to cool off, I’m able to identify many of the colorful fish flitting through the coral. Deep down, I spot a green sea turtle, her shell like an intricate mosaic tile on the ocean floor. I admire her from a distance. (And I know the turtle is a “she” because she has a very short tail — another tidbit from my beach briefing.)

“Those 45 minutes that you spent on the beach with Oliver were a very important 45 minutes,” Tim Lara, owner of Hawaiian Paddle Sports, later tells me. He founded the Maui-based eco-tour company in 2010. “One time when I was guiding, I had guests who didn’t know there was a Hawaiian people, or a Hawaiian language — and they’d been to Hawaii 10 times.” Tim wants to fix that. In addition to ocean safety and marine-naturalist certification, all his guides receive cultural training. Their job, he says, is about more than taking people out on the ocean and showing them a whale or sea turtle.

Occasionally, someone complains. Why did they have to stand on the beach learning when they could have been in the water, snorkeling? “I never apologize for what we do,” Tim says. “When I moved to Maui, I was taught the concept of kuleana, which essentially means that for every privilege we have in life, we have a responsibility connected to it. One thing we say on our tours is that if we have the privilege of playing in the ocean, we have the responsibility of caring for the ocean.”

Like so many places around the world, Hawaii has endured its share of hardships in recent years. The August 2023 wildfire that levelled Maui’s historic town of Lahaina was the most devastating natural disaster in modern Hawaiian history. And although it is dependent on tourism, the state’s popularity has also become a problem (tourists outnumber locals seven to one). The steady influx of visitors threatens the integrity of beaches, reefs and hiking trails. In the aftermath of the wildfires, visitors are being invited to return, but by an industry that is encouraging a more regenerative tourism model — one that gives more than it takes. The hope, Tim says, is that visitors will embrace the concept of mālama (to care for) when they come, and help protect and preserve Hawaii.

For Tim, using his tours to teach visitors about ocean conservation comes easily. He spent much of his childhood in the water around the Florida Keys, where his father was a diver and an environmentalist (Tim joined him in protests against offshore drilling when he was a kid). But teaching visitors about a culture and language not his own is another thing entirely, and he wanted to make sure he got it right. That’s where Iokepa Nae‘ole (known as Kepa) comes in.

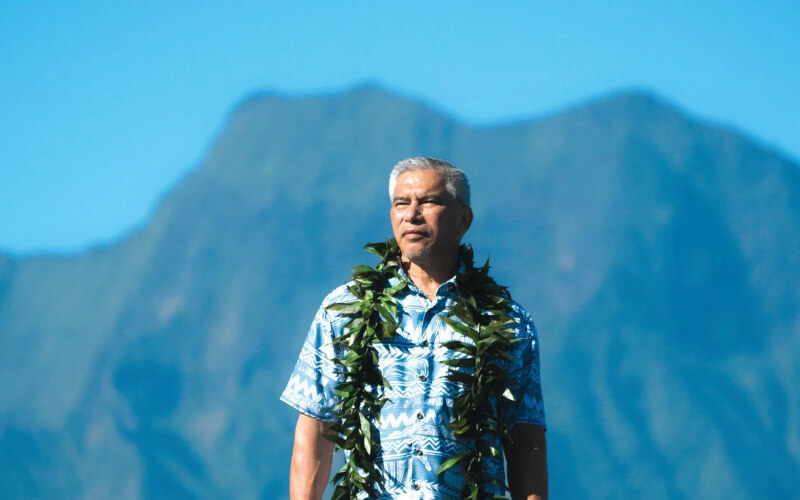

The two met about 20 years ago, at the Hawaiian Canoe Club, where Kepa taught Tim how to paddle an outrigger. Before long, Kepa became Hawaiian Paddle Sports’ cultural advisor, and every year he trains the tour company’s guides. “I tell them, ‘You’ve got a humongous responsibility on your shoulders,’” he says. “With every guest who comes through, you need to do what you can to get the message of kuleana to them so they can take it home and spread it there.”

When Kepa used to take visitors out onto the ocean, he did the same thing he now teaches Tim’s guides to do, sharing Hawaiian legends and language and trying to help them feel a connection to both the culture and the environment. “We just have to chip away at it, one visitor at a time,” he says. “When they got out of my canoe, I wanted them to go home and realize that the products they consume, the cars they drive, the lifestyle that they choose affects us, because it is our sea that is suffering from microplastics and global warming and rising sea levels. We want people to realize that it’s not just us, we can’t fight it here alone.” (Tim has had notes from travelers inspired to launch river cleanups at home after their tours.)

Another of Kepa’s missions is to dispel the many misconceptions visitors have about Hawaii, particularly the common belief that it’s a playground. “This is not Disneyland,” he says. Recently, a group of tourists spotted a baby humpback whale that had become separated from its mother near Waikīkī. One woman jumped into the water and tried to climb on the distressed calf’s back. (Ocean safety teams eventually arrived to guide the calf back out into the ocean.) “For me, there’s a simple way to differentiate between a tourist and a visitor,” Kepa says. “A tourist will try to ride a lost baby whale or a sea turtle, or drive by a burned-out town to take pictures of it. A visitor will come and ask how they can help.”

Many are doing exactly that. Hawaii is the perfect embodiment of transformative travel — you’re bound to be affected by your visit. “There is an intangible benefit to being here,” Kepa says. “I think that’s what drives people to share their stories when they go home. It’s that feeling that they have, that aloha, that they find for this place.” But inevitably, your visit also leaves its mark. Every newcomer to these pristine islands has changed them in some way — only now, some visitors are helping to ensure those changes are positive ones.

To date, 23,613 people have signed the Pono Pledge, a sustainable-tourism commitment created in 2019 that’s based on the word pono, which means righteous, respectful, responsible. But visitors can do more than sign the pledge. They can participate in a beach cleanup in Maui before heading out onto the ocean (an activity that’s often part of a Hawaiian Paddle Sports tour) or contribute to reforestation efforts during a hike or help clear invasive species while walking in Volcanoes National Park. That was the option I chose when I left Maui to explore the Island of Hawaii.

In Volcanoes National Park, I meet Jane and Paul Field outside the Kīlauea Visitor Center, loppers in hand. Once a week, for the past 11 years, the retired couple have taken volunteers — usually a mix of both local regulars and visitors to the island — out into the forest to hack away at the long stalks of Himalayan yellow ginger that are crowding out native plants on the forest floor beneath the towering Ohia trees.

“I jokingly tell people that my wife and I fell in love with this park before we fell in love with each other,” Paul says. When they first started hiking in the forest, the pair admired the ginger, which was planted in the park decades ago simply because it was pretty. Then, they learned the truth — and decided to do something about it. First, on their own, and then, since they clearly weren’t going to give up, the Center’s Interpretation Division helped them set up a volunteer program.

“Ginger is a water and nutrient hog,” Paul explains as we shoulder through the stalks, shearing them off a foot from the ground so the couple can return and dust the cuts with herbicide to prevent the plants from growing back. “The forest floor should be covered with little ferns.”

The work is meditative, nothing but the sound of rhythmic lopping and the occasional trill of the ‘Oma‘o thrush as we uncover the forest that should be. The ginger stalks give way with a satisfying crunch, like snapping spears of asparagus. “This forest doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world,” Jane says. “If we lose it, it’s not just a loss for us, it’s a loss for everybody on the planet.” I will only spend a few hours in this peaceful, restorative rainforest, but I feel an urgency to help preserve it. Piles of mangled ginger amass at my feet and I push deeper into the dense wall of green. I think of kuleana, and I’m reluctant to stop hacking when Paul tells us it’s time to go — just let me tackle this last patch!

There are about 15,000 acres of ginger in the park, and Jane and Paul have probably cleared about 50 acres of it, returning to push the encroaching ginger back every other year from those same acres. “We know we’ll never get rid of it,” Paul says. “But when we return to an area we’ve done, we see how the forest is responding and growing. We see new plants, and seedlings that are now taller and stronger. It’s very rewarding.”

Every year, Paul and Jane encounter visitors who, like them, have fallen in love with the park and return to spend a few hours battling ginger in the forest during their vacations on the island. Here, as on the beaches of Maui, the concept of kuleana, of privilege and responsibility, might be the one thing that can protect and preserve Hawaii for both its residents and its visitors. “We love sharing our park with other people,” Jane says. “I can’t imagine a better day than one spent in this native forest — and, if you’re going to be here, you might as well be doing something useful.”

Where to Stay

FAIRMONT KEA LANI, MAUI

Fairmont Kea Lani guests are greeted in a luxurious open-air lobby with melodic waterfalls surrounded by lush gardens. In addition to its three pools and white-sand beach, the hotel features a new immersive Hawaiian cultural center and offers daily opportunities for guests to connect with the Hawaiian way of life, from sampling island family recipes at Kō, its award-winning restaurant, to learning to paddle an outrigger canoe.

Where to Eat

UMEKES FISH MARKET BAR & GRILL, HAWAI ‘ I

Local photographer Ricky-Thomas Serikawa recommends a poke bowl with poi (mashed taro root) on the side at Umekes in Kailua-Kona.

“I love going to Umekes because their fish is straight out of Kona waters.”

What to Do

ON THE ISLAND OF HAWAII

Pay a visit to Laulima Nature Center in Hilo, a community hub that hosts free conservation events; roast your own sustainable coffee beans at Kona Joe’s on the Kona Coast; or take a tour of Kona Sea Salt farm, which supports the Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project to remove fishing nets and plastics from reefs and shorelines.